Monthly Archives: January 2013

Sunshine and Shadow – January 2013

– near the Gowanus Canal, near where the dolphin got trapped and died the other day –

“end stop and frisk; hands off the kids!”

Standing on what used to be the boardwalk of a much wider beach. The debris has been removed, and all that is left are the concrete supports.

They’ve caught sand in the wind and formed a sort of dune;

within it are scraps of tile and vases, smashed in the storm.

The neighborhood today was silent, frozen, locked-down.

Buildings still burned out, power still out in places – sand everywhere.

There’s still a long road ahead.

Hiding in the Shadows – Finding New Amsterdam

I have a great love for urban exploring – digging up obscure places and events in the annals of New York. Places like the Staten Island Ship Graveyard, Dead Horse Bay, the Mansion of King Zog, the 1964 World’s Fair Grounds, et al…

In many ways, the following topic is the most obscured. Barely anything physical remains of the Dutch colonial era- it exists now only in resonant names, culture, and perhaps, in ghosts that ply the dense streets of this city.

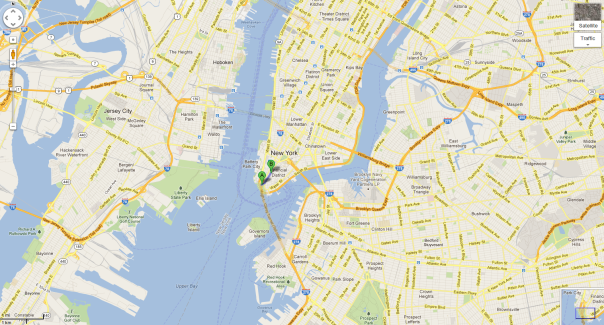

The tip of Manhattan Island, today’s Financial District, from the East River in the 1660’s. The World Trade Center is now roughly in the middle of the frame

Even though the Dutch Republic controlled New York for barely more than a generation, it left an indelible mark on the psyche of the city.

For centuries European nations sought control of the much coveted Northwest Passage, which was thought to allow a more direct sea route to Asia, allowing trade to bypass the arduous journey around Cape Horn or the Cape of Good Hope. When expeditions finally transited the route in the early 20th century, it had proven to be a pipe-dream – Arctic ice completely barred reasonable navigation until 2009, when the ice pack melted sufficiently to allow year-round passage.

The Dutch West India Company was founded as a conglomeration of merchants, explorers, and men of money to regulate and centralize colonial trade networks. As such, it became the de facto government of outposts throughout the world. It’s been said that the Company was akin to a modern global corporation – but with guns. Finding and controlling the Northwest Passage was at the top of the DWIC’s agenda. In 1609, they sent an English explorer, Henry Hudson, to scope out the North American continent and pursue any promising leads. After a long Atlantic voyage, Hudson came upon a very wide, protected bay, fed by a large river that penetrated deep into the interior – an obvious candidate for a Northwest Passage. Passing Manhattan island, Hudson made his way up his namesake river, as far as he could go. Disappointingly, it proved to be a dead-end. At least, however, he had found a source of a very valuable commodity at the time – beaver fur; a luxury item that could fetch high prices in Europe.

Former headquarters of the Dutch West India Company, in Amsterdam. It was from this building that the colony of New Amsterdam was chartered.

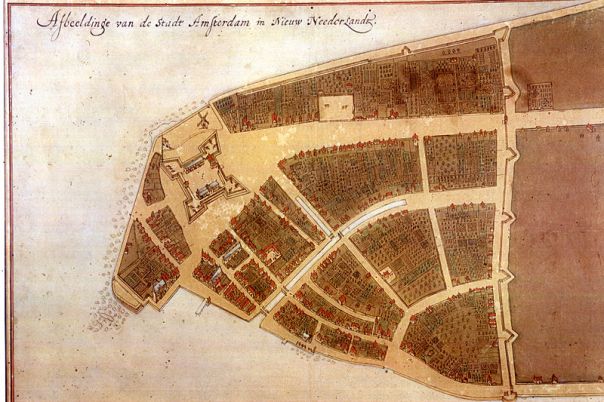

And so, over the following decades, Dutch settlers began arriving and trading. They covered a swath of remote outposts from what was known as the “South River” (The Delaware River) all the way past the “North River” (or the Hudson River, as it gradually became known). In the great harbor that Hudson had come upon, there were a handful of Europeans living on the very tip of Manhattan Island, and on “Noten Eylant” (now Governor’s Island). In 1624, the settlement, Nieuw-Amsterdam, was officially chartered as a colony of the Dutch Republic, and capital of the New Netherlands colonies. The Dutch, of course, were not alone in European designs of control of New World resources, and so very quickly, a fort was erected at what is now the Battery. Though plantations were scattered throughout the future five boroughs, and far beyond, the town was little more than Fort Amsterdam. One could walk from end to end in under 10 minutes, the distance between today’s Battery Park and Wall Street:

It was a reckless sort of person who would endure the dangers of the sea and then live on the very margins of civilization facing a highly uncertain future. It was a desperate sort of person that would go to such lengths to make a living or ensure a fortune in doing so. New Amsterdam became notoriously unruly. What’s more, it attracted settlers from all over the European world, including French Huguenots, Sephardic Jews, and of course, African slaves.

In addition, as was happening all along the Atlantic seaboard, the colonists made a poor first impression on the Indians. When one of the first directors of New Netherlands, Willem Kieft, demanded tribute from the local tribes, skirmishes broke out which led to a short, ugly war that still bears his name.

In response to Kieft’s lack of control, in 1647 the Dutch West India Company replaced him with Petrus (Peter) Stuyvesant, a veteran of conflicts in the Caribbean. With ambitious zeal, he razed houses at Fort Orange (Albany, NY) and drove out the Swedes from the banks of the Delaware River and founded the city of New Castle. It was Stuyvesant who dug the Heere Gracht, the canal that was later filled in and called Broad Street. And on the edge of town, he built the defenses that gave Wall Street its name.

The 1660 “Castello Plan” of New Amsterdam, which encompasses the area between “A” and “B” on the Google map above. Note the Wall and the canal that became Broad Street. Broadway is the wide thoroughfare extending from the fort. Once can also see Peter Stuyvesant’s “White Hall”, which gave its name to Whitehall Street

Former location of the Dutch canal, which was renamed Broad Street, after the polluted waterway was filled in.

The NY Stock Exchange is visible on the left.

He imposed a string of austere policies meant to whip the colony into shape. Crimes were more harshly punished, taverns were ordered closed on Sundays, and church attendance became mandatory. He certainly kept order, but was wholly unpopular. Some of his more extreme enforcements were met with strong retorts. When a ship of Sephardic Jews arrived from Brazil, he tried to turn them away until pressured by the Dutch West India Company to desist. When he tried to brutally suppress Quakerism in the village of Vlissingen (Flushing, Queens), he was met with the “Flushing Remonstrance”, a resistance that inspired the freedom of religion clause in the Bill of Rights.

The house of John Bowne, a noted Quaker, who left repression in New England for the Dutch colony of Vlissingen (Flushing). He was arrested by Peter Stuyvesant for having a Quaker meeting in this house in 1662. Outcry over the arrest led to the “Flushing Remonstrance” It is the second oldest structure in New York City,

With the English to the north and to the south, New Netherland was caught in the pincers, and England was eager to take over the entirety of the Atlantic coast. In late summer of 1664, their navy appeared in the harbor of New Amsterdam and demanded surrender. Stuyvesant made a call to arms, which fell on cold shoulders. The English offered free passage back to Europe for those who would not submit to their rule; but hardly anyone took them up on it. It has been said that the colonists didn’t care what nation ruled them, as long as they could make money.

And so, the colony went back to its business, now under the name of New York. Dutch custom, culture, and language persisted for generations before dwindling away. In fact, there were still native Dutch speakers at the time of the American Revolution more than a century later.

A few Dutch-era names rose to lasting prominence, and were counted among old patrician families that author Washington Irving called the “Knickerbockers”. Some of them are still very current – the Roosevelts and the Vanderbilts, for instance.

The backyard of St. Marks Church-in-the-Bowery, built in 1799 on the site of the family chapel of Stuyvesant’s 62-acre Bouwerij estate, now the heart of the gritty East Village. His remains are buried within.

The church sits askew of the Manhattan grid, recalling the country path that once passed by.

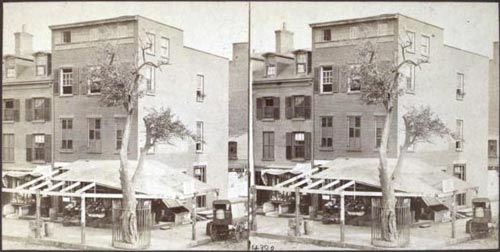

Stuyvesant lived out the final eight years of his life at his Bouwerij (plantation) in the fields outside the city. He is interred at St. Marks Church-in-the-Bowery, built in 1799 on the site of his family chapel. In 1867, one of his pear trees, now surrounded by the city at 13th Street and 3rd Avenue, succumbed to a horse cart accident. It was the final living remnant of New York’s Dutch origins.

The last tree of Stuyvesant’s estate, and the last living connection to New Amsterdam, at 13th Street and 3rd Avenue in the 1860’s, soon before it died. Note the large protective fence.

And so today, apart from some tavern and town hall foundations recently excavated around Hanover Square (you can view them from a window in the sidewalk), the vestiges of the city’s Dutch era exist only in names and spirit. New York lived up to New Amsterdam’s mercantile ambitions, and then some. For better or worse, it is still a place where money talks, regardless of your origins or beliefs.

And the names – those who live in the region hear them every day – names like Haarlem, Breukelen, Conyne Eylandt (named for its rabbits), Tappan Zee, Hell Gate, New Utrecht, Flushing, Van Wyck Expressway, and the “Kills” (creeks) that appear in town and river names up and down the Hudson Valley…

Stuyvesant’s Bouwerij became the notoriously scruffy Bowery, and the raucous East Village now covers his plantation. The diagonal country lane passing in front of his church, now named Stuyvesant Street, is a solitary hold-out against the 1811 Manhattan grid plan. His name is still everywhere – high schools, housing developments, libraries, etc.

250 years after New Amsterdam, the coarsely planned colonial streets gave birth to the skyscraper and to the world’s financial capital. The narrow lanes, meant for small houses, now host some of the tallest buildings in the world, which have obscured the ground perpetually in shadow. On quiet blocks, or at night, squeezed between the concrete canyons, you can almost hear the clogged feet on packed earth, the cantor of a passing horse, or the whispers in Dutch. All historical facts aside, this is where one can feel closest to the distant outpost on the edge of the world that once was.

Amazingly, the streets of New Amsterdam were never widened to accept 20th century skyscraper construction.

Appropriately, in the end, one of my most striking New York moments was not here, but in old Amsterdam, in the train station, when I heard a departure announcement for Breukelen. Full circle around the elusive story of Dutch New York.

The Crappiest Cameras of the Digital Age

HAPPY NEW YEAR! All best wishes to thee and thine.

This is a re-run of an article I wrote for onefive4gallery.com, a collective of artists from a multitude of disciplines. Check them out!

In recent years, vintage toy cameras have been gaining artistic appeal. Why?….

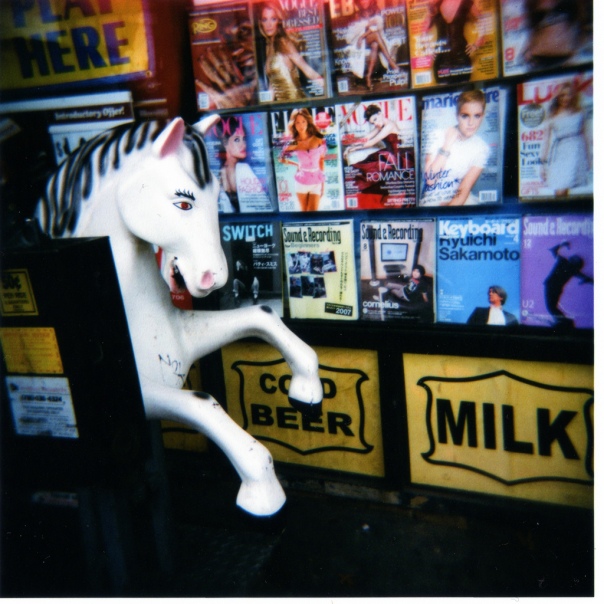

World’s Fair Grounds, Queens, NYC

Holga, Fuji Superia Reala 100

The Holga, the Diana, and others… they were among the lamest cameras of the ’60’s and ’80’s – cheap plastic give-aways that kids would save cereal box-tops for. The bottom pile of an increasingly sophisticated artform, when photography was becoming precise and razor sharp in its aesthetic and production. In their time, a camera with a plastic lens, dubious aperture settings and a vague focusing system, was definitely not to be taken seriously.

Whether it likes it or not, the present always looks towards the past. So in our digital world, with our digital aesthetics, it is inevitable that we begin to see nostalgia, and even to seek nostalgia, in what we look at and listen to. This is why music, trends, and art tend to repeat themselves every few generations or so.

These weak pieces of plastic have, for the first time, begun to mean something to the art of photography. We have come to expect perfection in our pictures, but the hearts of many of us still hold dear the imperfect images of our memories.

Long Lake, the Adirondacks, New York

Holga, Fuji Astia 100, cross-processed

This is one of the basic appeals of a camera like the Holga or Diana. Pop in a roll of old-school 120 film and shoot the best you can without the benefit of a re-do. Then rush the roll to a lab and wait a small eternity for the turn-around- At first, all this ends in frustration- casting off precious dollars for 12 frames of failure. Eventually you get it right though, and begin to get pictures that many would say were shot decades ago – back in that world of memory.

Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal. Antwerp, Belgium

Diana, Ilford HP5 400

But this effect is now possible digitally- with apps like instagram, hipstamatic, etc. For now, the eye can still tell the difference between digital effect and real analog, but very soon, the two will be indistinguishable.Digital has far outpaced what film can do. So it goes- there’s no purist indignation here.

Then – what’s the point of having a love affair with analog film, and especially for cheapie plastic cameras?

Two reasons that come to mind:

1) There are no re-do’s. You have to get it right the first time. This frees the instinct to have full sway, and often, instinct is the best force we have. There are no fancy knobs and settings, no science. Just you and the light.

2) Also, the chemical properties of film are totally integral to the image produced. Each make of film has its own basic character that can’t be circumvented. Choosing the right film for your vision is like finding the right spice for a meal- once you start with it, it’s there to stay. And- analog processing is subject to temperature, time, and density- functions of the physical world. It’s a more dynamic, organic, process.

World’s Fair Grounds

Holga, Fuji Superia Reala 100

Careful re-makes of vintage toy cameras are sold all over the place now, and analog is definitely in fashion lately. It has all the trappings of a fad. Who knows if it will stick. Who cares?… It’s an endlessly fun art, and that’s all it really needs to be.

Amsterdam

Diana, Kodak Tri-X 400

Port de Hal, Brussels –

Diana, Kodak Tri-X 400

New Paltz, NY

Holga, Kodak Portra 400

Staten Island Ship Graveyard

Diana, Kodak Portra 400

Central Park, NYC

Diana – Ilford HP5 400

Long Lake, the Adirondacks, NY

Holga, Fuji Astia 100, cross-processed

Astoria, NYC – Holga, Kodak Portra 400

Occupy Wall Street, NYC

Diana, Kodak Portra 400

For more of my analog, toy camera pics: